Ukraine's defence technology industry has grown in the three years since Russia's invasion, continuing to innovate despite the threat of reduced US assistance.

As the escalation of the Russian invasion in Ukraine enters its fourth year, experts say European investors are starting to put their money behind Ukrainian military technology start-ups in massive numbers.

Venture capitalists like Deborah Fairchild and Justin Zeefe from Green Flag have seen "marked" interest from potential investors in Scandinavian countries, the Baltics, and the United Kingdom since US President Donald Trump took office last month.

"That is extremely noteworthy because… it's mostly from European countries that are going to have or have an acute need for maintaining a defensive perimeter," Fairchild said.

This increase in interest follows a wider trend of investors clamouring to enter a booming military technology market with exploded growth.

According to experts, what was largely a Soviet-inherited industry before the full-scale invasion is now a healthy landscape where roughly 500 arms producers go from battleground-tested prototype to scaled technology in as little as three months.

How did the Ukrainians get so innovative?

In the first year of the full-scale invasion, Ukrainians heavily relied on stingers, javelins, HIMARS artillery rocket launchers missiles and the odd NATO weapon kit to fight back against the Russians, according to Daniel Bilak, partner at the legal firm Kinstellar and volunteer soldier with the Ukrainian forces.

A failed Ukrainian counteroffensive in 2023 demonstrated that the Russians had more troops and more control of the skies than their forces, so they had to find another way to stay competitive, he continued.

"The only way we could defeat [the Russians] was through technological advancement," Bilak said.

In order to do so, the Ukrainian government allocated more than 50 per cent of government expenditures to the military, bringing their spending up to 20 times the pre-invasion level, reaching $30.8 billion (€29.4 billion) in 2023, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

The Ukrainian government expedited its procurement process to match. Using the so-called "Danish Model," EU countries now directly finance certified Ukrainian defence companies that manufacture weapons on the ground.

All experts said the fastest approval from prototype to certified military weapon is three to six months when during peacetime, it would’ve taken over a year, something Bilak describes as an “incredible development” for start-ups.

"Our military tech is just miles from where everyone else is, nobody can innovate as quickly as we can because we have to," Bilak said.

The Ukrainian government set aside some of that defence funding for Brave1, a "united coordinational platform" that has provided more than 470 grants worth 1.3 billion hryvnias (€29 million) to defence startups and provides them with “organisational and informational support".

Much of the grant money has gone towards drone and ballistic missile technologies.

Another revenue stream for the Ukrainian defence tech industry comes from crowdfunding, Fairchild said. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s platform, United24, raised over 13 billion hryvnias (€298 million) with donors from over 130 countries.

Some of their projects are geared at defence innovation, like a fundraiser for terrestrial robotic platforms and robots to de-mine the country’s government-controlled territory.

"There are millions and millions that are being put into thousands of small workshops all over Ukraine," Fairchild said. "This country has an incredible network behind the scenes".

The year of the drone

Olena Bilousova, the lead of military research at the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) said one stand-out military technology sector is Ukraine’s growing drone industry, which she estimates accounts for 25 per cent of the country’s military weapons supply.

Drones became an "alternative" to artillery weapons when they were in short supply in the early days of the war, Bilousova continued.

"It’s just a good alternative to traditional types of weapons because it’s something that we can do quickly," she said.

Ukraine went from having up to 5,000 drones at the start of the invasion to producing an estimated 4 million drones in 2024, an October report from KSE found.

There’s now a national portfolio of specialised drones, like carrier drones that are platforms to deploy other drones, target drones for testing, electronic warfare drones to disrupt enemy communications and kamikaze drones that deliver precise strikes.

In a sea of innovations, AI-powered swarm technology that lets drones coordinate attacks without human operators is "one of the most innovative trends," in the sector, KSE reported.

One of the challenges that’s left for the drone industry now is to make sure that they can scale up and have enough to maintain the frontlines, Bilak added.

"[Drones are] basically a resource that… you just go through it like tissue paper," he said. "And as a result, you will see more and more investment into these drones".

Loss of American support painful but not the end

According to a support tracker from the German think tank Kiel Institute, the United States is the largest single donor to Ukraine, giving roughly €114.149 billion since 2022.

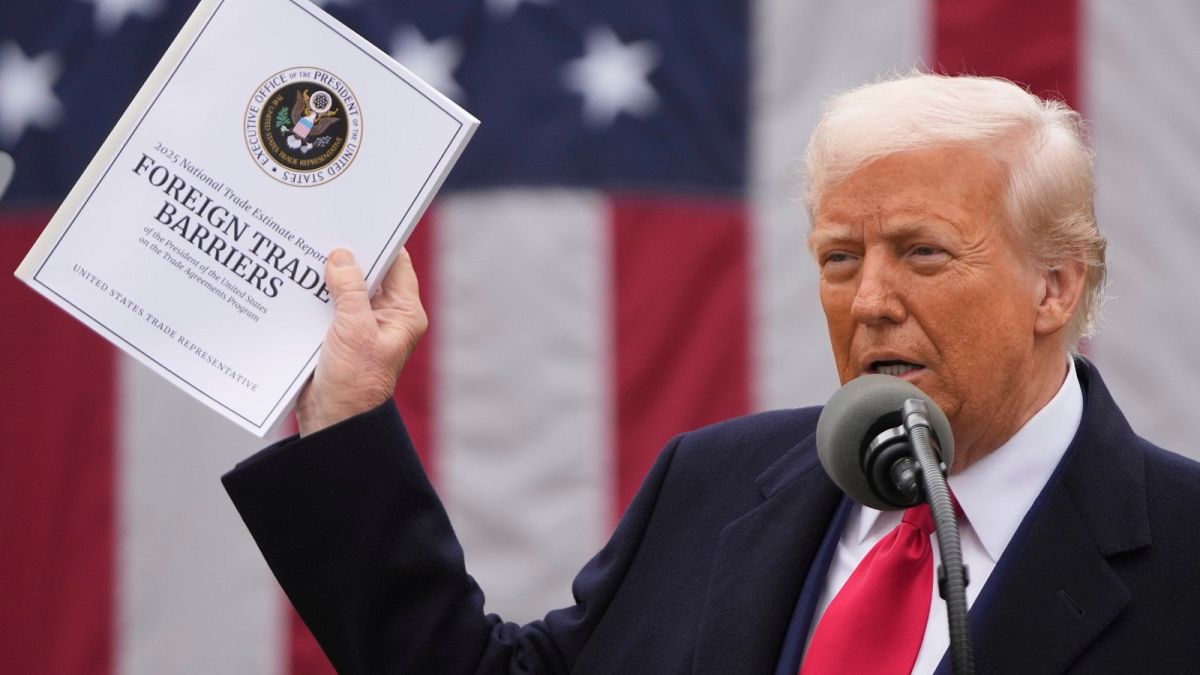

President Trump has asked Ukraine to pay them back for this aid with a guarantee of $500 billion (€487.7 billion) in rare earth minerals, which Zelenskyy had initially rebuked but is now reportedly working out with Washington.

If Ukraine wanted to move away from US-based aid, the Bruegel Institute said in a recent report that the dollar values are small enough for Europe to replace the US in full by spending "only another 0.12 per cent of its GDP".

Fairchild believes the Ukrainian military technology industry will find a way to fill any possible holes because their forces have done it before.

For example, the Ukrainian Magura drone equipped with SeeDragon missiles shotdown a couple of Russian helicopters and dozens of ships in their Black Sea fleet, a feat by the Ukrainian military that Fairchild believes is often overlooked.

"It’s all Ukrainian-made weapons that are doing that," she said. "I am optimistic that they will be able to fill in the gap… not to say that [an American retreat] wouldn’t be painful, but they’re not going to say 'okay we’re done'".

1 month ago

15

1 month ago

15

We deliver critical software at unparalleled value and speed to help your business thrive

We deliver critical software at unparalleled value and speed to help your business thrive

English (US) ·

English (US) ·