Tanikawa diverged from haiku and other traditions, and explored the poetic, not only in the repetitive music of the spoken word but also the magic hidden in little things.

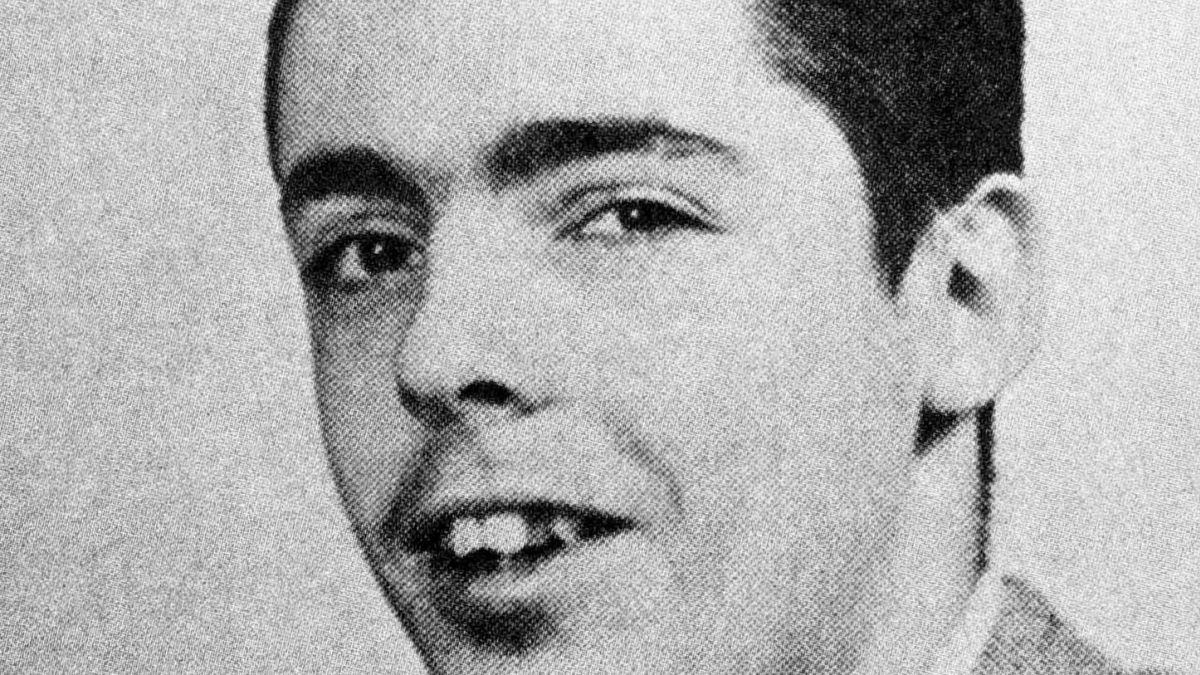

Shuntaro Tanikawa, who pioneered modern Japanese poetry, has died aged 92.

Tanikawa, who translated the Peanuts comic strip and penned the lyrics for the theme song of the animation series Astro Boy, died on 13 November, his son Kensaku Tanikawa said today. He said his father died at a Tokyo hospital due to old age.

Shuntaro Tanikawa stunned the literary world with his 1952 debut “Two Billion Light Years of Solitude,” a bold look at the cosmic in daily life. Written before Gabriel García Márquez’ “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” it became a bestseller.

Tanikawa’s “Kotoba Asobi Uta,” or “Word Play Songs,” is a rhythmical experiment in juxtaposing words that sound similar, such as “kappa,” a mythical animal and “rappa,” a horn, that makes for a joyful singsong compilation, filled with alliterations and onomatopoeia.

“For me, the Japanese language is the ground. Like a plant, I place my roots, drink in the nutrients of the Japanese language, sprouting leaves, flowers and bearing fruit,” he said in a 2022 interview with AP.

Tanikawa explored the poetic, not only in the repetitive music of the spoken word but also the magic hidden in little things.

In every work Tanikawa tackled, including the script for Kon Ichikawa’s Tokyo Olympiad, a documentary film of the 1964 Tokyo Games, the respectful love for the beauty of the Japanese language resonates.

He also translated Mother Goose, Maurice Sendak and Leo Lionni. Tanikawa has in turn been widely translated, including English, Chinese and various European languages.

Some of his works were made into picture books for children, and they are often featured in Japanese school textbooks. He also incorporated Japanese words derived from foreign origins into his poems like Coca-Cola.

In his prose poem with that title, in which a boy is opening a Coke can, he wrote: “If, for instance, he saw the infinite universe that started or ended at the tip of his can, he was totally unaware of it. One might be able to opine that he named every bit of the unknown about to swallow him with all the vocabulary he could muster, which included his future vocabulary that was yet dormant in his subconscious.”

Tanikawa was born in 1931, a son of philosopher Tetsuzo Tanikawa, and began writing poetry in his teens, circulating with the famous poets of that era, like Makoto Ooka and Shuji Terayama.

He said he used to think poems descended like an inspiration from the heavens. But, as he grew older, he felt the poems welling up from the ground.

Tanikawa said he wasn’t afraid of death, implying he perhaps meant to write a poem about that experience, too.

“I am more curious about where I will go when I die. It’s a different world, right? Of course, I don’t want pain. I don’t want to die after major surgery or anything. I just want to die, all of a sudden,” he said.

He is survived by his son, musician Kensaku Tanikawa and daughter Shino and several grandchildren.

4 months ago

40

4 months ago

40

We deliver critical software at unparalleled value and speed to help your business thrive

We deliver critical software at unparalleled value and speed to help your business thrive

English (US) ·

English (US) ·