As Lebanon confronts the aftermath of another war with Israel, non-sectarian MP Michel Moawad discusses the new president, Hezbollah, and his hope for rebuilding a country ravaged by conflict, sectarian violence, and corruption.

On 9 January this year, the Lebanese parliament formally elected Joseph Aoun as president, breaking a sectarian political stalemate that had run for more than two years. He succeeded Michael Aoun — no relation — who left office in October 2022 after a six-year term wracked by economic meltdown and political instability, as well as the devastating Beirut port explosion of August 2020.

Michael Moawad MP, leader of the self-proclaimed “non-confessional, third way” Independence Movement, Harakat al-Istiqlal, has plenty of direct experience of his country’s sectarian strife. His father René, a prominent independent politician, served as president in 1989 for just 17 days before he was assassinated with a 250kg car bomb that exploded next to his motorcade.

His assassination came less than a fortnight after multiple factions in Lebanon signed the Taif Peace Agreement, which was designed to bring 15 years of sectarian civil war to an end.

“After my father's assassination, unfortunately, everything went the wrong way,” Moawad told Euronews from his office in Beirut, “he was assassinated because he was elected to bring back peace amongst Lebanese and reconciliation, the same need we still have today”.

Lebanon is the Middle East’s most religiously diverse country. Its population is almost evenly split between Christians, Sunni Muslims, and Shia Muslims, while around 4.5% of citizens identify asDruze. And making the country work despite its divisions has proven a Herculean task.

Despite the Lebanese parliament ratifying the Taif Agreement in November 1989, the years that followed were marked by political paralysis and security nightmares. The country was occupied by Israeli forces in the south and Syrian forces in the northeast, and political assassinations were commonplace.

But far from dissuading him from entering the exhausting, often dangerous political arena, Moawad explains that his father’s murder “played a pivotal role in my decision to go to come back to the country” after studying in France.

He added that his father left an “essential legacy that I came back to fight for”.

'A lonely space'

The Independence Movement was formed in 2005 during the Cedar Revolution, a largely peaceful uprising in the wake of the assassination of former prime minister Rafik al Hariri in which protesters demanded the withdrawal of the 14,000 Syrian troops and intelligence officers then stationed in Lebanon.

Moawad singles out self-government as a central tenet of his party’s founding.

“We've been fighting to reclaim our sovereignty … since the end of the war,” Moawad told Euronews, complaining that there was a binary choice “between corrupt liberal structures vs far-left reformists.” He says Harakat al-Istiqlal is instead a politically syncretic entity, weaving Lebanese nationalism together with liberal, reformist policies.

“If I had to compare us to European parties, we would be very nationalist-sovereignist on the one hand, we’re very much pro the constitution of Lebanon, while also wanting to renew it. Then we certainly would also be a reformist, social-liberal party economically.”

The Cedar Revolution succeeded in kicking Syrian forces out of Lebanon, an event some saw as the country’s first glimpse of full sovereignty for the first time in decades. Israeli forces had withdrawn from southern Lebanon five years prior to beyond the contentious “Blue Line” border, as established by a UN resolution.

However, the Shia militia and political party Hezbollah remained a dominant force in Lebanon, and the de facto authority in most of southern Lebanon and south Beirut. It also retained close financial and political links with the Assad regime in Damascus, and with Iranian officials in Tehran.

“We passed through the Syrian era and then into the Iranian era,” concludes Moawad.

Hezbollah has not only maintained its military dominance, but has been a powerful force in the Lebanese parliament, with 15 of 128 seats. That may not sound like many, but the parliament is elected according to the “confessional” quota system, under which different Muslim and Druze groups and Christians are allocated an equal ratio of seats. This means Hezbollah controls more than half of the Shia-allotted seats.

According to tradition, the president is a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of parliament a Shia Muslim.

Moawad sees this system as part of the problem, and told Euronews his party believes in “the fundamental idea that confessional politics is leading to a blockage”.

When Moawad put himself forward for the presidency in 2022, he was blocked by Hezbollah MPs and their allies from the largely pro-Assad, pro-Iranian “8 March” coalition.

The Lebanese president is elected by parliament and officially must secure two-thirds in the first round of voting to be elected; in subsequent rounds that falls to a simple majority of 65. However, in practice, a quorum of two-thirds of members is required to elect a president.

“To avoid the risk of me having 65 votes, [the alliance] broke the quorum and left the chamber,” Moawad claims. “We believe that that is contrary to the spirit of that constitution."

MPs opposed to Moawad at the time called the quorum a “democratic tool” to prevent the election of a “defiantcandidate”.

Moawad understands his beliefs put him at odds with many from all sects who cling on to Lebanon’s entrenched system. “The real difficulty of it is not only the political landscape, but the ability to create a structure that is not … either been built on the idea of the supreme leader or built on militias that became political parties.”

“It's a lonely space and it's very difficult to keep a national presence,” he admits.

The end of Hezbollah hegemony?

On 8 October 2023, Hezbollah launched a barrage of rockets into the Israeli-occupied Sheba’a Farms region on the Lebanese border, in response to the first of the deadly Israeli strikes on Gaza that followed the Hamas-led 7 October attacks.

Over the subsequent 15 months, the conflict between Hezbollah and Israel intensified, with Israel invading southern Lebanon and launching unprecedented airstrikes on parts of central Beirut. The ensuing war has decimated much of Hezbollah’s leadership and military capacity.

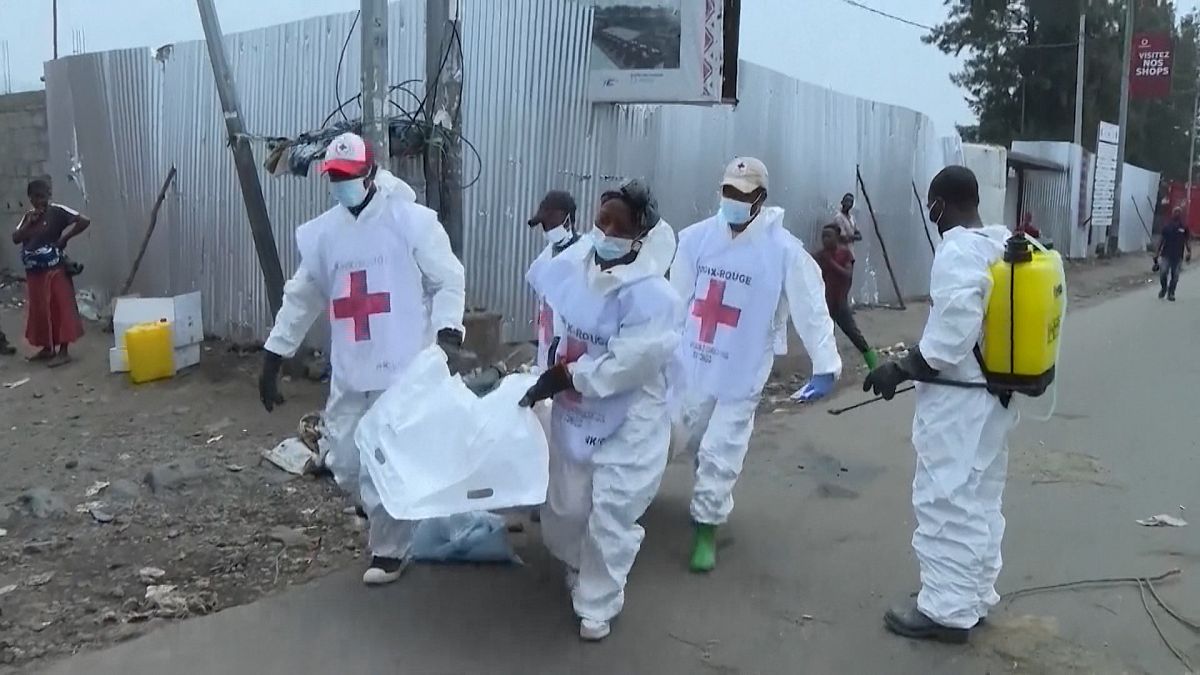

When Israel and Hezbollah signed a ceasefire agreement on 27 November 2024, at least4,000 Lebanese citizens had been killed — though Moawad and many others believe the real number is much higher — and more than 1.2 million displaced.

The deal gave Hezbollah until 26 January to end its armed presence in the area between the Blue Line and the Litani river, some 30km to the north. Israeli forces also had to withdraw from the area over the same period. At the time of writing, Israeli forces remain in parts of southern Lebanon, claiming Hezbollah has not disarmed.

While Moawad insists that “Israel must withdraw from our land, towns, and villages,” he also lays blame with Hezbollah and its “partners in crime” not only for the latest war, but for the previous conflict in 2006.

“We did our best to tell them, choose Lebanon over Iran,” he says, “but they didn’t want to hear anything. That led us to a complete destruction.”

However, with Hezbollah severely weakened, Iran’s power receding, and the fall of al-Assad, Moawad has hopes of ending the stalemate.

“I think we have, despite all the bloodshed and despite all the destruction, and despite Lebanon in limbo, we do have today an opportunity”.

The road ahead

When Aoun – who is also commander of the Lebanese Armed Forces – spoke to the nation in his inaugural address, his message was stark: “If we want to build a nation, we must all be under the roof of law and justice.”

“There will be no more mafias or security islands, no more … money laundering, no more drug trafficking, no more interference in the judicial system … no more immunity for criminals and the corrupt”. He also promised that the Lebanese army would hold a “monopoly” on arms, a declaration many listeners took as an unsubtle swipe at Hezbollah.

“We're finally turning the page towards a new Lebanon,” Moawad told Euronews.

As things stand, he hopes that the next elections will see his party exponentially increase its number of parliamentary seats from the two that it currently holds. In the meantime, Lebanon still faces monumental challenges. Since January 2023, the Lebanese pound has slid from 1,600 against the Euro to more than 93,000.

“It's a very fine balance,” explains Moawad. “The old is dead, but the new is not yet born.” As an example of the challenge ahead, he points to the cost of rebuilding after the latest war.

“The direct cost of that reconstruction — direct, I'm not talking about the indirect cost on the economy, I'm talking about the physical destruction — is about $10 billion (€9.6 bn),” he sighs. “We have a state budget, overall budget, of $3 billion (€2.9 bn)”.

Then there are the social challenges, he says, not least “national reconciliation,” and the task of “making it clear to the Shia community that our battle is not against the Shia community, but against Hezbollah's hegemonic project”.

Still, the future of Lebanon is about more than just one sect. “We believe that a modern Lebanon cannot be built only on confessional political parties that represent their confessions. There needs to be a voice for the modern, diverse Lebanon.”

It’s a monumental and daunting challenge, but one Moawad and allies seem determined to pursue.

“We're not going to solve our problems in two days. But yes, now there is a path for hope.”

6 hours ago

2

6 hours ago

2

We deliver critical software at unparalleled value and speed to help your business thrive

We deliver critical software at unparalleled value and speed to help your business thrive

English (US) ·

English (US) ·